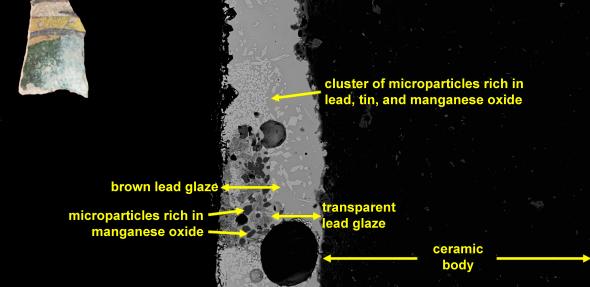

Image showing the microstructure of a glazed ceramic sample dating to the early Islamic period (late 8th to 9th centuries CE) by scanning electron microscopy

Admired in museums worldwide, Islamic glazes are considered to be a revolution in ceramic technology. Their repercussion is noticeable in Italian majolica, French and English creamware, and more generally in the emergence of glazed wares as a global phenomenon since the medieval period. This project will challenge the extant model on the beginning and spread of Islamic glazes, which asserts that they were all derived from the Middle East and spread with Arab expansion, and that new technologies were adopted passively by conquered societies. The diffusion of opaque glaze to al-Andalus (Islamic Iberia) is often used as a case in point.

The problem with this model is that it is based on small datasets and large assumptions. The received narrative dates the invention of opaque glaze in the 9th century AD and then jumps to the 12th century, where everything from lead glaze to polychrome-painted glaze is subsumed under ‘Islamic tradition’. Did this myriad of glaze technologies arise from a single, opaque glaze technology, and were they transferred directly from East to West? Or, have a range of glaze technologies been present but overlooked owing to the art-historical focus on opaque glaze?

This project will examine, for the first time, the evidence from Central Asia because glaze production in Central Asia only started after the Arab conquest and opaque glaze was not part of the repertoire. Given the region’s involvement in the Silk Road trade, its links with Sassanid, Chinese, and Byzantine glaze will be specifically investigated. The new data will be compared with examples from al-Andalus – in more detail than has heretofore been attempted – to explore the technological transfer and cultural interactions involved in the making of Islamic glazes.

This project will include a variety of glazed ware types dating to the 9th to 13th centuries CE from different regions of Central Asia, resulting from the collaboration with the UNESCO International Institute for Central Asian Studies. A multi-disciplinary research framework is devised, which features a new, standardised schema to frame the reconstruction of glaze traditions, the use of a wide range of analytical methods to characterise different aspects of glaze technologies, the construction of a database for new and legacy data, the application of statistical analyses, and reference to anthropological theories on knowledge exchange and technological change.

The results are expected to create a new model that will redefine what ‘Islamic glazes’ truly entail. This new definition will not only focus on reconstructing all the technologies that were used, but also highlight the multitude of social processes, different interactions between East and West, in this case manifested in the Silk Road connection, involved in making Islamic glazes; and by extension new insights into the process of Islamisation. The Central Asian data will also represent this missing link that connects the Islamic glazes with contemporaneous glaze traditions. This will allow for making the first, major step of understanding how glazed ware emerged as a global phenomenon, which had such fundamental impact on our production and consumption habit until today.

McDonald Institute Renfrew Fellowship