Where’s the best place to get a good night’s sleep in Ancient Sumer? The easiest way to go from the market square to the main temple? What are the best festivals? Any tips on the local delicacies? The University of Cambridge has worked in collaboration with Esagil Games to create new classroom resources for primary children which add colour to the teaching of everyday life in Ancient Mesopotamia.

Dr Augusta McMahon and Dr Marie Besnier, both experts in the language and civilisation of Ancient Mesopotamia, have worked together to produce new illustrations, maps, and information into a travel guide to the ancient Sumerian cities. Packed full of engaging hints and tips, they are the centrepiece of the project “Traveling in Ancient Sumer – Urban studies and Sensory Archaeology to recreate Ancient Sumer” which aims to introduce new facets of the Ancient World to children.

The research collaboration was funded by the University of Cambridge Arts and Humanities Impact Fund in 2021-2022, hosted in the Department of Archaeology, and supported by Cambridge Enterprise.

As part of the project, we have developed, together with Esagil Games, this picture database. It contains masterpieces of Sumerian art which you can use to illustrate your courses if you choose to introduce Ancient Sumer to your pupils. Each picture comes with few lines of explanation to put them back in context and point out why they are representative in the history of Ancient Sumer. Full credits and captions are found below.

Now the classroom workshops and materials will be taken forward by Esagil Games, who work directly with Cambridgeshire schools to run interactive classroom workshops, presented by Marie – see Sumer in the National Curriculum – Esagil Games).

If you have questions and comments about the picture database, need further information, or are interested in our sessions for your class, please get in touch with Marie at: marie@esagil.co.uk.

--

| Title | Date and place | Museum and (short) description |

| Warka Mask | ca 3000 – Uruk |

Baghdad Museum

(Life-size; limestone) |

| Uruk Vase | ca 3000 – Uruk |

Baghdad Museum

(H: 105cm; alabaster) |

|

Sumerian Worshipper from

Ešnunna |

ca 2700 - Ešnunna |

Metropolitan Museum

(H: 29.5, gypsum) |

| Sumerian Worshipper | ca 2500 – ? | Liebieghaus, Frankfurt |

| Ebih-Il | ca 2500 – Mari |

Louvre Museum

(H: 52; alabaster) |

|

Mace of Messalim, king of

Kiš |

ca 2550 - Lagaš |

Louvre Museum

(19 x 16; limestone) |

| Sumerians at work: in the | ca 2500 – Tell al’Ubaid |

British Museum

(H : ~ 15; shell) |

|

Ur-Nanshe Relief

(perforated relief) |

ca 2500 – Lagaš |

Louvre Museum

(39x46,50x6,50; limestone) |

|

Relief of Dudu (perforated

relief) |

ca 2450 – Lagaš |

Louvre Museum

(25 x 23 x 8; bitumen) |

| Stele of the vultures | ca 2450 – Girsu |

Louvre Museum

(restored but fragmentary; originalH~180; L~130; limestone) |

| Head of Sargon | ca 2300 – Nineveh |

Baghdad Museum

(H: 30,5; Bronze) |

| Seated Gudea | ca 2100 – Lagaš |

Louvre Museum

(46x33x22,50 ; diorite) |

| Foundation peg of Gudea | ca 2100 – Lagaš |

Museum of art, Cleveland

(H: 20; bronze) |

| Clay nail of Gudea | ca 2100 – Lagaš |

Walters Art Museum

(16 x 4,5; diam of head: 6,9; baked clay) |

|

Ziqqurrat – drawing

(reconstruction) |

ca 2100 – Ur | |

| Photo of the Ur ziqqurrat | At the moment of its discovery |

The Warka-mask: This stone-mask was probably hung on the temple wall or put on the face of a statue (probably the goddess Inanna). It originally had a wig and inlaid eyes and eyebrows (bitumen and lapis-lazuli).

The Uruk Vase: It depicts on four registers a procession to present offerings to the goddess Inanna (goddess of Uruk, and goddess of love and war). The lower registers depicts the countryside, animals and plants; theinhabitants of Uruk are represented on the medium register: they are bearing all kinds of products for the ceremony. On the upper register, the king is approaching the goddess; behind her, inher temple (figured by poles), are heaps of various offerings.

Sumerian worshippers: Those statues are typical of Sumerian art; they are men and women (even couples),commoners (all professions) and kings. They were put in the temples to represent the person before the gods,in a state of constant prayer.

They share common features: they wear a garment (skirt or dress) made of lamb wool, called kaunakes (easily recognisable because locks of wool are depicted over the whole garment or on the fringe); their hands arecrossed on the chest (prayer gesture); they have big “blue” incrusted eyes (bitumen and lapis-lazuli); they show anexpression of contentment, even happiness; most of them bear an inscription which states their names andfunctions.

Ebih-Il, the superintendent of Mari, is one of the finest examples of those statues. He is sitting on areed basket.

King Eannatum of Lagaš is also the one depicted on the Stele of the Vultures.

Sumerians at work - in the dairy: Shell inlaid decorations on bitumen or black stone are very common inSumerian art, to depict friezes of animals or everydaylife scenes.

Mace of Messalim, king of Kiš: It bears an inscription : “Mesalim, king of Kiš, built the temple of Ningirsu”.Imdugud, the lion-headed eagle, emblem of Ningirsu is depicted on it.

Inscribed / decorated maces are common in Sumerian art. They were the weapons of gods and kings; many were put in the temples with votive inscriptions.

Perforated reliefs: Perforated reliefs are very common in Sumerian art: they were probably nailed on the walls (oftemples) to commemorate important deeds. However, a recent theory understands them as locks to temple doors,since one of them has been found in situ in the ancient city of Mari. Scenes on perforated reliefs are depicted onregisters – often 2 of them - as is often the case in Sumerian art.

- The relief of Dudu: The main character depicted on two registers is Dudu, the priest of the god Ningirsu (god of Lagaš). The main scene on the upper register represents Imdugud, the lion-headedeagle fighting with lions.

- The relief of Ur-Nanshe: On the upper register, the king of Lagaš, Ur-Nanshe (first of his dynasty) is depicted as a builder – he bears a basket that contains bricks on his head; the inscription explains that he is building the temple of Ningirsu, the god of Lagaš. On the lower register, theking is feasting with members of his family, probably to inaugurate the temple he has just built. Thecuneiform inscription names the people attending the feast and tells that the king has imported wood fromDilmun (Oman or Bahrein) to build this temple. This is one of the very first mentions to long-distance trade.

The Stele of the vultures: The stele recalls the conflict between the cities of Lagaš and Umma and the victoryof the king of Lagaš, Eannatum (grand-son of Ur-Nanshe). It is the most ancient known historical narrative. The stlele owns its name from a flock of vultures flying over the corpses after the battle.

One side depicts the “historical” event that is the battle itself on several registers: Eannatum leading his soldiers is represented both marching and on his charriot holding a long spear. A mass phalanx of helmeted warriors ofLagaš tramples over the corpses of the soldiers from Umma.

The other side depicts the “mythological” facts that is the intervention of the god Ningirsu in favour of Eannatum: the god helds the huge battle-net where the ennemies are prisonners.

Head of Sargon: Sargon is the first Akkadian ruler, and ruled over all Mesopotamia after having defeated the Sumerian city-states. He is the founder of a dynasty and the builder of the first “empire”.

The seated Gudea: Gudea was the king (lit. prince) of Lagaš; he is famous because archaeologists have found some 90 statues ofhim that were put in the temples; he is either standing or sitting but is always dressed the same way, and always has his hand crossed over his chest, to pray his god, Ningirsu. His most famous deed was to built anew the temple of Ningirsu.

Foundation pegs and clay nails:

Mostly made of bronze, foundation pegs (which have the human shape of a deity or king). They were symbolically marking the grounds and limits of a temple. They were put in the foundations of the temples, eitherhammered in a corner of the temple or buried together with other objects, usually a stone tablet and / or cylinderseals or weapons. Those foundation deposits were essential to remind to all who is the builder of the temple andto curse anybody who would delete the temple. This is why most foundation pegs were inscribed. Foundationpegs are very common in Sumerian art, and many of them were unearthed. This foundation peg represents a kneeling god, recognizable by the horns on his tiara.

The use of clay nails was very similar to the one of foundation pegs: they were hammered in the walls of thetemples in order to remind to all who built the temple and for whom. As was the case for foundation pegs, theinscriptions written on them were not visible: they were intended for the gods.

This one recalls the building of the temple of Ningirsu, god of Lagaš, by the king Gudea.

The ziqqurrat:

The Sumerian staged-tower concretises the link between even and earth. The ziggurat was the heart of aSumerian city and its most impressive monument. There was a shrine on its top but we do not know for sure whatit looked like or which ceremonies took place up there. Ziggurats were made of mud-bricks and this is why they are so poorly preserved nowadays and why so few is known about theorganisation of the upper stages.

The first ziggurat dates from the end of the Sumerian period (so-called Ur III empire) but ziggurat were built during the whole history of Mesopotamia until the half of I millennium BC.

(More about ziqqurrat, temples and religious life in a school session: see https://esagil.co.uk/teachers-corner/gods-and-temples-of-sumer/ and… when you visit the city of Ur with your pupils! https://esagil.co.uk/travel-in-sumer-the-book/ur-sumer-booming-capital-c...)

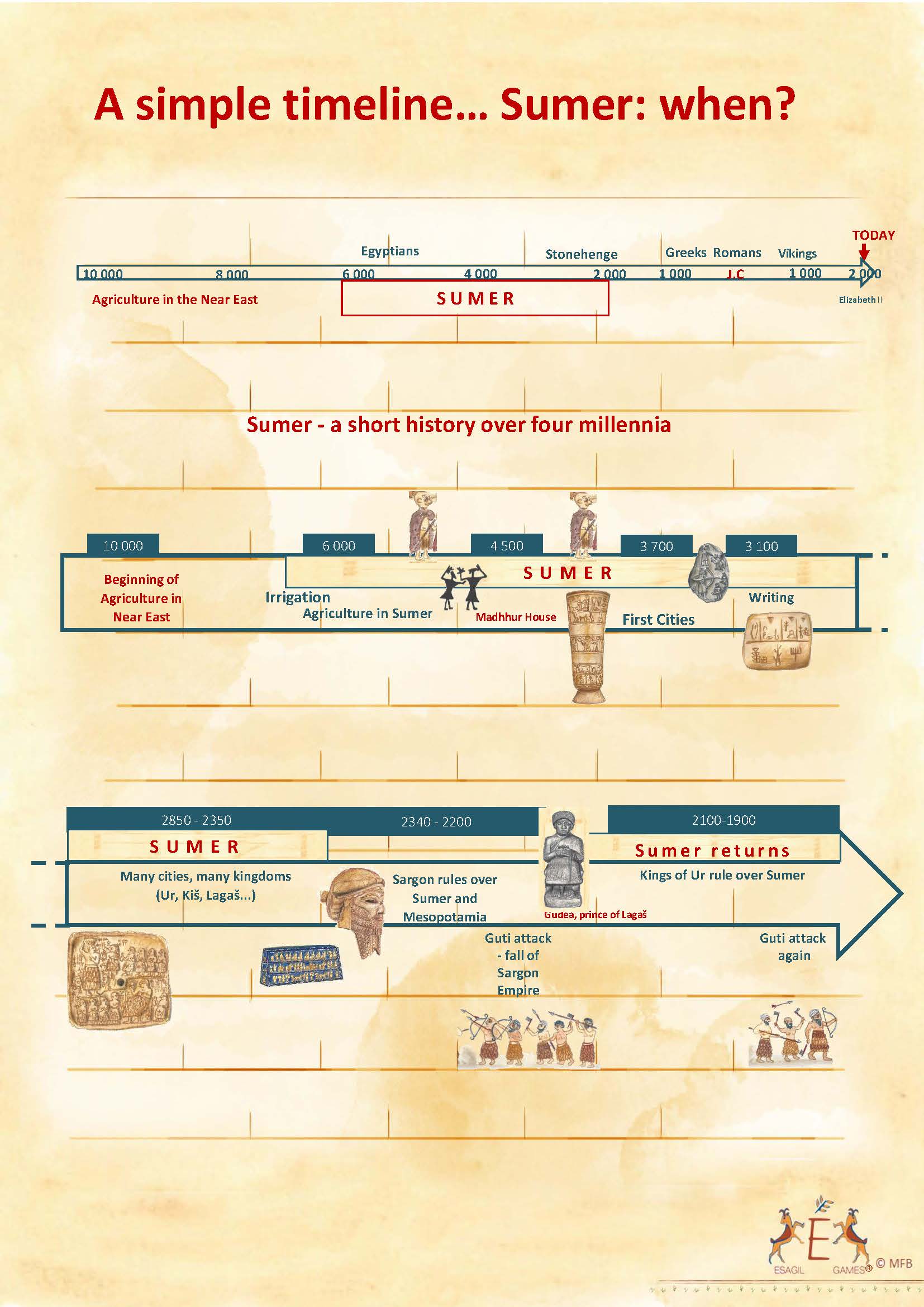

Download a pdf of the Sumer timeline

OBJECTS FROM THE ROYAL CEMETERY OF UR (CA 2500)

The royal cemetery of Ur was excavated between 1922 and 1934. Among hundreds of modest burials, the archaeologist, Sir Leonard Woolley, distinguished 16 of them as “royal” because of their richness and more elaborated construction and organisation. Some of the most beautiful Sumerian pieces of art were found there. They date from the mid-third millennium BC.

Most objects from the tombs are now in the British Museum or in the University of Pennsylvania Museum.

| Title | All objects here from the British Museum |

| Lyre | H:110; W:97); wood and silver |

| Meskalamdug helmet | H:23; electrum |

| Queen Puabi’s jewellery | gold, silver, cornaline and lapis-lazuli |

| Gaming board | 27 x 12 |

| Helmet on a soldier’s head | bronze |

| Ostrich egg vase | life size |

| Ram standing in front of a golden plant |

Composite sculpture made of wood, gold, silver, shell andlapis- lazuli (H: 50); they are two of them; Woolley has firstnamed them

“Ram caught in a thicket” after Genesis 22, v: 13. |

| The “Standard of Ur” | (5 Pictures) |

| “Standard” box and banquet side | |

| “Standard” war side | |

|

“Standard” details

• Banquet side: herders and fisherman (medium register) • Banquet side: the musician and the singer (upper register) |

- Lyre: Three lyres were discovered in the royal tombs of Ur, two of them in the grave of Queen Puabi. They are made of wood and covered in sheets of silver. They also have a silver or golden cast bull’s head attheir front.

- Gaming board: Made of wood inlaid with a mosaic of shell, bone, lapis-lazuli and red limestone; rulesare still mysterious but some archaeologists tried to sort them out. More gaming boards were found inthe tombs.

- Helmet on a soldier’s head: the soldier was fully equiped and buried with his king.

- Ostrich-egg vase: Example of an exotic and luxury product for the royal court. Several ostricheggs were found in the royal graves.

- The standard of Ur: One of the master-pieces of Sumerian art. A wooden box (H: 21.7; L: 50.4; W: 11.6to 5.6) with inlaid pannels of imagery made of lapis-lazuli, shells, and red limestones. The rectangularsides depict a scene of battle and a scene of banquet, each of them on 3 registers to read from the lowerto the upper one, where the king is clearly distinguished as the tallest figure. On the banquet side, the Sumerian society is represented in its whole, from the humble peasants who bear sacks of grains andbunches of reeds, to the nobles who are cheering with the king. On the war side, the battle is depicted onthe lower register, where charriots are driving over the bodies of the ennemies; soldiers are marching andprisonners are presented to the king. We do not know for sure what the object itself was; surely not a “standard” but the name was kept till nowadays.

(More about the Standard of Ur in a school session: see https://esagil.co.uk/teachers- corner/first-steps-in-sumer/)

WRITING: TABLETS AND CYLINDER SEALS

(More about writing, pictograms, cylinder seals and… Gudea in a school session: see https://esagil.co.uk/teachers-corner/learn-sumerian-with-gudea-prince-of...)

| Title | Date and place | Museum |

| Hollow clay sphere | ca 3300 – Susa | Louvre Museum |

| Pictogram tablet | ca 3100 - Uruk | British Museum |

| Archaïc tablet | ca 3100 – Unknown | Louvre Museum |

| Inscription of king Ur- | ca 2100 – Ur |

British Museum

(Black stone) |

| Cylinder seal + impression (Cylinder | ca 3100 – Uruk | British Museum |

- Hollow clay sphere and tokens: Tokens were placed inside a hollow sphere; cylinder seals were rolledover it to prove whom could access the records of on the surface of the sphere. Tokens were of different sizes and shapes to represent different quantities or products. The records could only be known bybreaking open the sphere. Sometimes tokens were also impressed on the surface of the clay sphere.

- Pictogram tablet: Tokens were replaced by simple, schematic drawings: pictographic signs. The “tokensystem” and pictographic signs have developped together. It is not certain that one preceded the otherone.

- Archaïc tablet: As more and more information is given on the tablet, the pictographic signs are getting more abstract and some phonetic signs are added. The shape of the signs were also adapted to being written with a rectangular-ended stylus made out of reed. As a result, the strokes that compose a signwere wedge-shaped. This is how the cuneiform writing got its name.

- Example of a royal inscription: For the goddess Inanna, Lady of Eanna, his lady, Ur-Nammu, mightyman, king of Ur, king of the land of Sumer and Akkad, for her, he has built and restored her temple.

- Cylinder seals: the cylinders, most often made of stone, that were carved with a design so that theywere rolled out on clay a continuous impression in relief is produced. They are usually about 2-3cm highand 1.5-2cm diameter. The scenes on cylinder seals depict mythological episodes as well as everyday life moments; the name and title of their owners were also carved on them as soon as the cuneiform writing developed. Each cylinder seal is unique. They wereused to state ownership on tablets or sealed jar or locked doors etc. The cylinder seal here is the one of Queen Puabi (lapis-lazuli). It was placed in her grave (see royalcemetery). It represents the king and the queen feasting on two regisers.

CREDITS FOR THE PICTURES:

All images in presented here are:

- either property of Esagil®Games

- or public domain

- or under a Creative Commons license for sharing (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/): links to the author and license are provided for each images under those conditions.

- All objects from the British Museum are under Creative Common License CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

| Title | Credits | |

| Warka Mask | Drawing by ©Vicki Herring for Esagil®Games | |

| Uruk Vase | Drawing by ©F. Muià for Esagil®Games | |

|

Sumerian Worshipper

from Ešnunna |

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mesopot

amia_male_worshiper_2750-2600_B.C.jpg |

|

| Sumerian Worshipper | Public domain | |

|

Sumerian Worshipper

(King Eannatum) |

Drawing by ©Vicki Herring for Esagil®Games | |

| Ebih-Il | Public domain | |

|

Mace of Messalim, king

of Kiš |

Public domain | |

|

Sumerians at work: in

the dairy |

Photo by ©MFB for Esagil®Games | |

|

Ur-Nanshe Relief

(perforated relief) |

Drawing by ©F. Muià for Esagil®Games | |

|

Relief of Dudu

(perforated relief) |

Public domain | |

| Stele of the vultures | Drawing by ©F. Muià for Esagil®Games | |

|

Stele of the vultures

(“historical side”) |

Drawing by ©F. Muià for Esagil®Games | |

|

Stele of the vultures

(detail – vultures) |

Drawing by ©F. Muià for Esagil®Games | |

|

Stele of the vultures

(Ningirsu) |

Drawing by ©F. Muià for Esagil®Games | |

| Head of Sargon | Drawing by ©F. Muià for Esagil®Games | |

| Seated Gudea | Drawing by ©F. Muià for Esagil®Games | |

|

Foundation peg of

Gudea |

Public domain | |

| Clay nail of Gudea | Public domain |

|

Ziqqurrat – drawing

(reconstruction) |

Drawing by ©F. Muià for Esagil®Games | |

|

Photo of the Ur

ziqqurrat |

Public domain | |

| Lyre | Photo by ©MFB for Esagil®Games | |

| Meskalamdug helmet | Photo by ©MFB for Esagil®Games | |

| Queen Puabi’sjewellery | Drawing by ©Vicki Herring for Esagil®Games | |

| Gaming board | Photo by ©MFB for Esagil®Games | |

|

Helmet on a soldier’s

head |

Photo by ©MFB for Esagil®Games | |

| Ostrich egg vase | Drawing by ©Vicki Herring for Esagil®Games | |

|

Ram standing in frontof

a golden plant |

Photo by ©MFB for Esagil®Games | |

|

“Standard” box and

banquet side |

©The Trustees of the British Museum | |

| “Standard” war side | ©The Trustees of the British Museum | |

|

Standard detail: war side – marchingsoldiers

(medium register) |

Photo by ©MFB for Esagil®Games | |

|

Standard detail: banquet side –herders and the fisherman

(medium register) |

©The Trustees of the British Museum | |

|

Standard detail: banquet side - the musician and thesinger

(upper register) |

©The Trustees of the British Museum | |

| Hollow clay sphere and tokens | © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons /CC- | |

| Pictogram tablet | ©The Trustees of the British Museum | |

| Archaïc tablet | Drawing by ©F. Muià for Esagil®Games | |

|

Inscription of king Ur-

Nammu |

©The Trustees of the British Museum | |

|

Cylinder seal +

impression (Puabi) |

©The Trustees of the British Museum |