History of Research at Amarna

The 18th Century: First Depiction

Scientific interest in Amarna dates back over 200 years to the turn of the 18th century when French scholars accompanied Bonaparte’s military and exploratory campaign into Egypt in 1798/1799. They produced the first partial map of the site, published in the famous Description de l’Égypte. Although Akhetaten was never a ‘lost city’, as people had been living on the site for generations, the origins of the sprawling mud-brick ruins and the identity of its founder king were at this time unknown.

The 19th Century: Pioneer Excavation and Recording

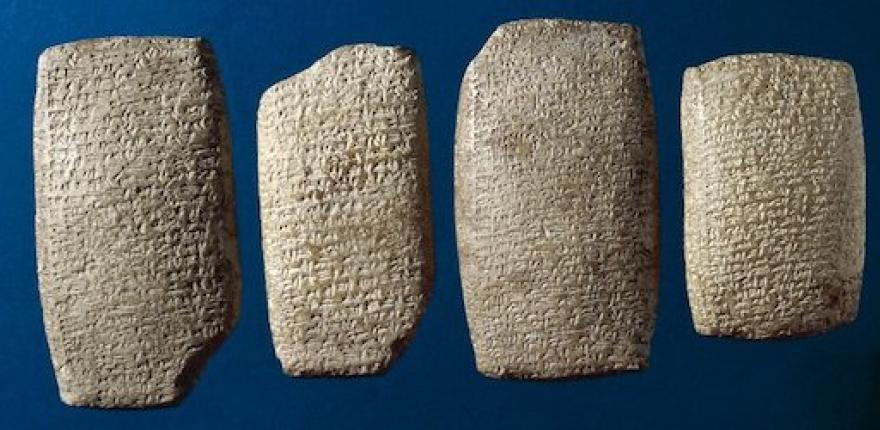

The 1800s saw further mapping by English Egyptologist John Gardner Wilkinson (1824, 1826), followed by the German K. Richard Lepsius (1840s), and the first attempts to record the texts and decoration in the Amarna tombs. In the 1880s, French Egyptologists Urbain Bouriant and Alessandro Barsanti partially cleared the Amarna Royal Tomb, by this time already robbed. Around 1887 the Amarna Letters were discovered by villagers in the Central City. Written on clay tablets in Akkadian Cuneiform, the letters revealed remarkable diplomatic correspondence between Egypt, Mesopotamia and lands around the Eastern Mediterranean.

British archaeologist Flinders Petrie turned his interest to Amarna in the 1890s. He undertook sample excavations in the centre of the ancient city and produced a new, more extensive survey of the site. Petrie was assisted by a young Howard Carter, who would later go on to excavate the Tomb of Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings.

The 20th Century: Expansion and Consolidation

From the early 1900s, archaeologists began to expand their sights, recognising that the remarkable preservation of housing areas at Amarna would allow them to study ancient urban life. Most of ancient Egypt’s towns and cities are now lost or difficult to access, buried beneath modern settlements or under field systems along the riverbanks. Amarna is different. Lying open and easily accessible on the desert plain, it offers us a kind of time capsule of a single generation of people who lived over 3000 years ago. Very few archaeological sites anywhere in the world provide such a complete view of an ancient city, with large expanses of temples, houses, cemeteries and the original landscape relatively intact.

From 1911–1914, a German team from the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft worked at Amarna. Today, their work is best known for the discovery of the painted bust of Nefertiti in a workshop south of the Central City, but their focus was really on recording ancient housing.

Between 1921 and 1936, the London-based Egypt Exploration Society excavated widely across Amarna, including in the housing suburbs, the Workmen’s Village, at the North Palace and North Riverside Palace, the outlying temples, and within the Central City. The early excavators relied heavily on a large team of support staff, including men, women and children from the local communities of Tell Beni Amran (El-Till) and El-Hagg Qandil. Specialist workmen, initially trained in excavation methods by Flinders Petrie, were also brought in from the village of Quft near Luxor.

This first wave of excavation at Amarna focused largely on clearing buildings and mapping their remains. The work progressed rapidly, with huge areas uncovered very quickly, in keeping with excavation standards of the time. Unfortunately, such was the speed of the work that much important information was lost. Those records that were kept, especially architectural drawings, were often of a high standard, however, and the early excavations produced an important set of building plans, particularly of houses, that now serve as an atlas of ancient Egyptian housing. Many of the areas they worked at have since been lost under agriculture or settlement, making these records an invaluable source of information of what was once present.

From the 1960s, archaeology around the world began to change and better fieldwork methodologies developed. Archaeologists began to focus on applying careful methods of excavation, recovering as much ancient material as possible, no matter how ‘mundane’. In Egypt, Amarna became one of the flagship sites for this new approach.

In 1977 Barry Kemp CBE, Emeritus Professor of the University of Cambridge, began a programme of survey and excavation at the site in co-operation with the Egyptian Government’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. Professor Kemp’s work ran under the auspices of the Egypt Exploration Society until 2007, and then through the McDonald Institute at the University of Cambridge. The Amarna Project brings together researchers from Egypt and around the world in fieldwork and research that aims to investigate, record, and protect the site for future generations.

The 21st Century: Collaborative Social Archaeology

Excavation today is combined with a detailed study of artefacts and environmental materials, including animal bones and plant remains, and with survey work to continue mapping the site. Amarna has become a case site for a kind of data-driven social archaeology that seeks to reconstruct the way cities appeared, functioned and were experienced by their inhabitants.

Community members from El-Hagg Qandil and Tell Beni Amran (El-Till) continue to make an invaluable contribution to the work, from excavating alongside archaeologists, sieving to look for the smallest remnants of human activity in the past, or helping to consolidate ancient monuments with new bricks and stone. Local members of the team also help with the logistics of running the dig house, helping the research run smoothly.