Major new publication of two volumes reveals ‘cosy domesticity’ of Bronze Age Must Farm settlement

Detailed monographs on thousands of artefacts pulled from the settlement at Must Farm reveals the surprisingly sophisticated domestic lives of Bronze Age Fen people, from home interiors to recipes, clothing, kitchenware and pets

Two volumes have been published today, as part of the McDonald Institute series of Monographs, detailing the Bronze Age settlement of Must Farm, which was engulfed in flames almost 3,000 years ago.

Must Farm, a late Bronze Age settlement, dates to around 850BC, with archaeologists from Cambridge Archaeological Unit unearthing four large wooden roundhouses and a square entranceway structure – all of which had been constructed on stilts above a slow-moving river.

The entire hamlet stood approximately two metres above the riverbed, with walkways bridging some of the main houses, and was surrounded by a two-metre-high fence of sharpened posts.

The settlement was less than a year old when it was destroyed by a catastrophic fire, with buildings and their contents collapsing into the muddy river below. The combination of charring and waterlogging led to exceptional preservation. The site has been described as “Britain’s Pompeii”.

The site was excavated as part of a project funded by Forterra, manufacturer of building supplies, and Historic England.

Years of research conducted on thousands of artefacts from the site have now shown that early Fen folk had surprisingly comfortable lifestyles, with domestic layouts similar to modern homes, meals of “honey-glazed venison” and clothes of fine flax linen, and even a recycling bin.

The settlement-on-stilts also contained a stack of spears with shafts over three metres long, as well as a necklace with beads from as far away as Denmark and Iran, and a human skull rendered smooth by touch.

Full findings from the Must Farm site – excavated by the Cambridge Archaeological Unit (CAU) in 2015-16 after its discovery on the edge of Whittlesey near Peterborough – are published in two reports, published and funded by Cambridge’s McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

“These people were confident and accomplished home-builders. They had a design that worked beautifully for an increasingly drowned landscape,” said CAU’s Mark Knight, report co-author and excavation director.

Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit

Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit

Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit

Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit

Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit

Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit

Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit

Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit

The ruins of five structures were uncovered, along with walkways and fencing, but the original settlement was likely twice as big – half the site was removed by 20th century quarrying – with researchers saying it may have held up to sixty occupants in family units.

The river running underneath the community would have been shallow, sluggish and thick with vegetation. This cushioned the scorched remains where they fell, creating an archaeological “mirror” of what had stood above – allowing researchers to map the layout of the structures.

One of the main roundhouses, with almost fifty square metres of floor space, appeared to have distinct activity zones comparable to rooms in a modern home.

Ceramic and wooden containers, including tiny cups, bowls, and large storage jars, were found in the northeast quadrant of “Structure One”, the location of a kitchen.

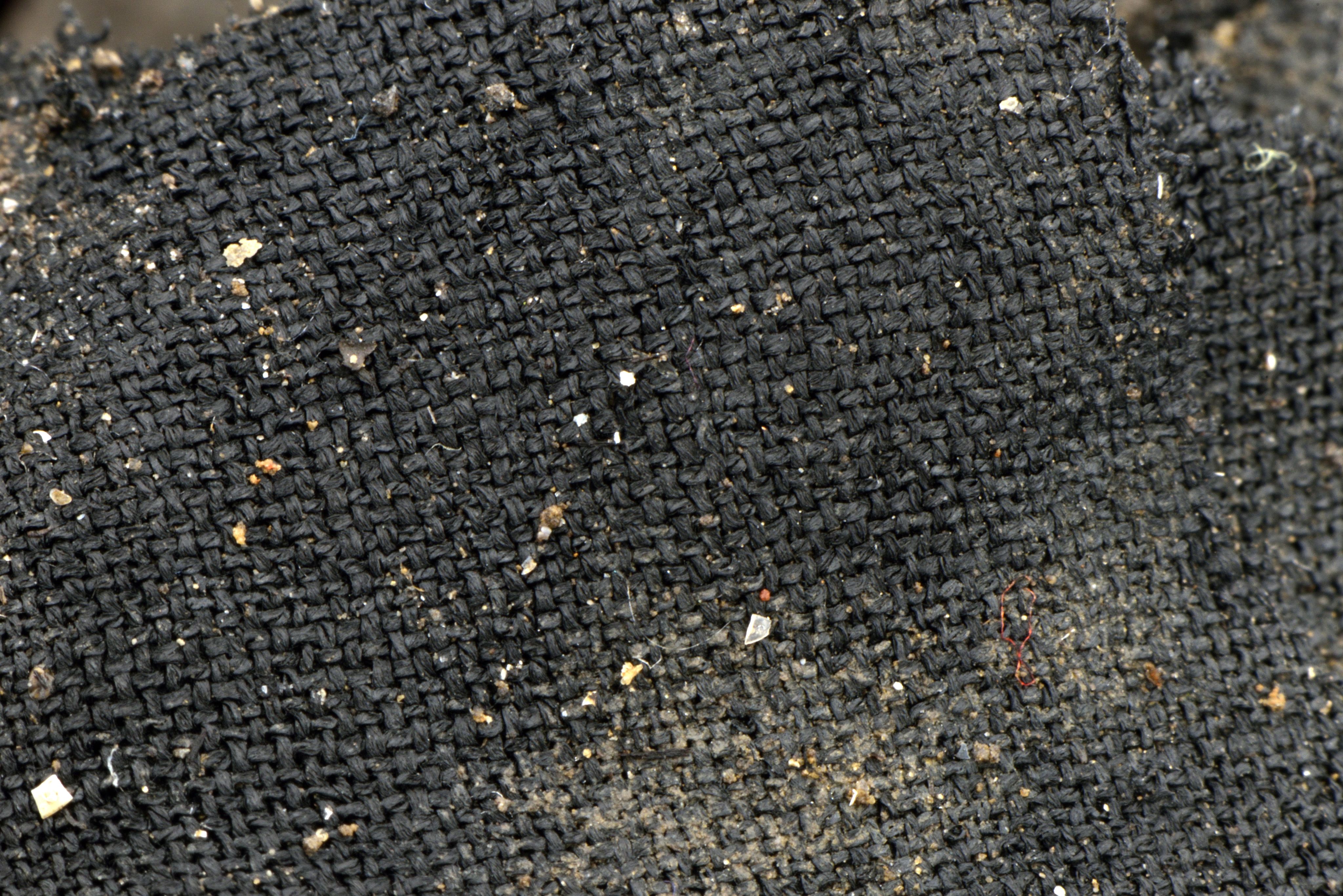

Metal tools were stored along the building’s eastern side, while the empty northwest area was probably reserved for sleeping. The southeast space had lots of cloth fragments, along with bobbins and loom weights.

The roundhouse’s southwest quadrant was reserved for keeping lambs indoors. There was no evidence of humans dying in the fire, but several young sheep had been trapped and burnt alive.

Household inventories were remarkably consistent. All the roundhouses contained a metalwork “tool kit” that included sickles (crop-harvesting blades) along with axes and curved “gouges” used to hack and chisel wood, as well as hand-held razors for cutting hair.

Most buildings had objects for making textiles and these finds are the finest of this period found in Europe.

Each roundhouse roof had three layers: insulating straw topped by turf and completed with clay – making them warm and waterproof but still well ventilated.

Encircling the footprint of each roundhouse were middens which included broken pots, butchered animal bone, and coprolites. Some human coprolites had parasite eggs, suggesting inhabitants struggled with intestinal worms.

Several small dog skulls suggest the animals were kept domestically, perhaps as pets but also to help flush out prey on a hunt. Dog coprolites show they fed on scraps from their owners’ meals.

Must Farm’s residents used the local woodlands – evidence suggests within a two-mile radius – to hunt boar and deer, graze sheep, and harvest crops such as wheat and flax as well as wood for construction. Waterways were vital for transporting all these materials.

The remains of nine log-boats, canoes hollowed from old tree trunks, were found upstream, dating from across the Bronze and into the Iron Age, included some that were contemporary to Must Farm.

A necklace of beads made from glass, amber, siltstone and shale had been lost in the fire. In fact, decorative beads were found right across the site.

The researchers say that, while the Bronze Age could be violent, and aspects of the site’s structure are clearly defensive, its location may be as much to do with resources. Spears found on site, up to 3.4 metres in length, as well as swords, were as likely to be used in animal hunts as on rival groups.

However, others think it more likely to have been an accident. If an internal fire took hold in one of the roundhouses, it would spread between the tightknit structures within minutes.

The full story can be found on the main University news site.

Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit

Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit

Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit

Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit

Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit

Image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit

'The richness of preservation and exemplary excavation at Must Farm make it the most significant example of daily life in the British Bronze Age and a landmark in modern archaeology. The McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research is honoured to have the opportunity to publish and co-fund the results of this work and we hope that both specialist and general readers will be enthralled by the combination of detailed scientific analyses alongside stunning visual imagery of the site'

'We are delighted to have been involved with the work at Must Farm. The insight it has given us into daily life in the Late Bronze Age is extraordinary. This project on a site of international significance is an outstanding example of the CAU’s consistently excellent work over more than three decades. We are grateful to the support of Forterra, Historic England and all those involved. We look forward to some of these remarkable artefacts being on display at Peterborough Museum, engaging the public with archaeology for decades to come.'

'Usually, at a Later Bronze Age period site you get pits, post-holes and maybe one or two really exciting metal finds. Convincing people that such places were once thriving settlements takes some imagination. But this time so much more has been preserved – we can actually see everyday life during the Bronze Age in the round – It’s prehistoric archaeology in 3 D with an unsurpassed finds assemblage both in terms of range and quantity. The vast breadth of scientific research within these two books gives unique insight how people lived in the Bronze Age.'

Published 20 March 2024

The text in this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License